The Supreme Court Could Restrict Doctors’ Rights to Sue on Behalf of Women Seeking Abortions

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | March 4, 2020 |

| Decision | June 29, 2020 |

| Petitioner Brief | June Medical Services, et al. |

| Respondent Brief | Stephen Russo (Louisiana) |

| Court Below |  Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals |

Case Decision

On June 29, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the abortion providers. The Louisiana law regulating abortion providers is unconstitutional.

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis.

Next week the Supreme Court will hear arguments from Louisiana and a group of medical providers about the legality of a Louisiana regulation on abortion providers. The law at issue requires that abortion providers have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of the locations where they perform abortions.

The law is not new to the Supreme Court, but the state defending it is. Texas passed the same law years back and in 2016 the Supreme Court ruled that it was illegal (Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt). The Constitution, the Court said, does not allow states to put a “substantial obstacle” on women’s access to abortion. The Texas law had done so, and the Court required Texas to take it off the books.

In this case, Louisiana will have to convince the Court that its law — or at least the effect of it — is different from the law in Texas. However, in an effort to avoid reaching that aspect of the case, Louisiana brought its own petition asking the Court to address a “standing” argument first.

Standing: Do the doctors have the right to bring this case?

The Constitution does not allow just anyone to bring a court case. The party bringing the court case must be the party who was harmed, or stands to be harmed, by the challenged action. If my cousin signed a deceitful credit card contract, I can’t bring a case against the credit card company. My cousin has to do it.

In this case, Louisiana argues that the doctors who brought the lawsuit do not have proper “standing.” The doctors claim the law violates their patients’ constitutional rights to have access to abortions. Louisiana says, well, then let the patients bring the suit; we don’t even know if the patients take issue with the law.

Supporters of the doctors’ position argue that Louisiana’s standing argument is inapplicable because in this case the doctors will in fact face injury under the law. Louisiana’s law punishes doctors who violate the law with imprisonment, civil liability, license revocation and fines. Even though the doctors are bringing claims based on the constitutional rights of their patients, the law still harms them directly.

Louisiana wants the Court to evaluate the standing inquiry based on a framework set out in a 2004 case, Kowalsi v. Tesmer. Kowalski limited third party standing to those cases in which the plaintiff (1) has a “close” relationship with the third party and (2) the third party suffers a “hindrance” to asserting her own rights. The state argues neither of these factors is satisfied here: the doctors do not have a “close” relationship with their patients (“the relationship between Plaintiffs and their patients is not only attenuated, but also riven with conflicts”) and the patients could very well bring the cases on their own (they can use pseudonyms to avoid public attention and they have in fact brought such challenges in the past).

Distinguishing Whole Woman’s Health

If the Court permits the doctors to bring the case, it will address the substance of the doctors’ appeal. Did the Fifth Circuit violate precedent (Whole Woman’s Health) in ruling the Louisiana law valid?

Louisiana’s task of distinguishing this case from Whole Woman’s Health is a tough one. The law is identical to the one Texas passed in Whole Woman’s Health. Both of them require doctors to get admitting privileges at hospitals within 30 miles of the locations where they perform abortions. Thus Louisiana has no chance based on the text of the law alone. The state must argue the effect of the law is different in Louisiana.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which sided with Louisiana, distinguished the cases. The Fifth Circuit said the factors that matter in conducting the legal analysis are different in Louisiana than they were in Texas.

The analysis

To address this case, a court must evaluate whether the state regulation imposes a “substantial obstacle” to women’s access to abortions. That’s the standard set out in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). To conduct the analysis, the court must weigh the state’s interest in creating the law against the burden to the woman in getting an abortion (Whole Woman’s Health). If the state has a strong interest and the burden on the woman is not great, the state can pass the law. And vice versa.

In Whole Woman’s Health, the Supreme Court evaluated the Texas law. It determined the Texas law provided absolutely no benefit to the state. It wasn’t helpful at all to require doctors to get hospital admitting privileges nearby. Plus, the burden on women’s access to abortion was substantial, the Court ruled. The law would make it very hard for doctors to qualify to provide abortions because getting hospital privileges in Texas is difficult. As a result, women would have to travel long distances to get abortions. Thus, the law could not stand.

The Fifth Circuit weighed these factors differently in reference to the Louisiana law. The Fifth Circuit said that the Louisiana law does provide a small medical benefit to the state of Louisiana. In Louisiana, the Fifth Circuit said, the credentialing of abortion providers was not up to par before the law, and the law requires them to get background checks and to satisfy other credentialing requirements. Slight benefit, but still a benefit, the Fifth Circuit ruled.

On the other side of the scales — the burden on women — the Fifth Circuit said the law will not cause the same “substantial burden” as it did in Texas. In Texas, the court said, the law was going to make it very hard for women to find credentialed providers, but in Louisiana it’s easier for doctors to get hospital privileges. In Whole Woman’s Health, there was proof that Texas abortion clinics were closing because of the law, but the same was not proven in Louisiana. The Fifth Circuit thus concluded that the Louisiana law could stand even though the same law in Texas was unconstitutional.

Questionable dive into the facts by the Fifth Circuit

Here is Louisiana’s big problem. Appeals courts like the Fifth Circuit aren’t supposed to open the factual record and start making their own analyses of the facts. They are generally supposed to trust the trial court on fact-finding and factual conclusions. The trial court is where all of the evidence is set out, and the theory is that trial courts are better suited to conduct factual analyses than appeals courts. Appeals courts only get what’s written in the record which is second-hand in a sense.

The trial court in this case — based on its primary review of the evidence — determined the facts regarding the Louisiana law (and its effects) were indistinguishable from the facts in Whole Woman’s Health. An appeals court would have to show the trial court was clearly wrong in order to overturn its factual conclusions. It’s a difficult standard to satisfy.

The doctors argue to the Court to overturn the Fifth Circuit decision to let the Louisiana law stand based on its error in diving into the facts rather than respecting the standard of review.

The U.S. government supports overruling Whole Woman’s Health

The federal government filed a brief in the case supporting Louisiana’s position. The government argued the Court should dismiss the case for lack of standing. Or if the Court reaches the merits, it should uphold the Fifth Circuit decision.

The government further said the Court may need to overrule Whole Woman’s Health. The brief argued that the Whole Woman’s Health balancing test may not be consistent with the standard set out in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which simply stated a state cannot place a “substantial obstacle” on abortion access. If a majority of the justices are looking for a way to uphold the Fifth Circuit decision without supporting the court’s factual reaching, they might like this hook.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on March 4, 2020.

DECISION ANALYSIS:

June 29, 2020

Supreme Court follows precedent in invalidating a Louisiana regulation on abortion providers

On June 29, 2020, in June Medical Services v. Russo, the Supreme Court ruled that a Louisiana law placing restrictions on abortion providers is unconstitutional. Chief Justice John Roberts provided the final vote to invalidate the law, leaving the conservative viewpoint in the minority for the third time in the last two weeks.

Background

The Louisiana law at issue in June Medical Services v. Russo required abortion providers to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of the locations where they perform abortions. A group of abortion providers challenged the law, arguing that the restriction was identical to a law out of Texas that the Supreme Court invalidated in 2016.

In the 2016 case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the Supreme Court invalidated a Texas law for providing an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to an abortion. Both the Texas law in Whole Woman’s Health and the Louisiana law in this case required abortion providers to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of where they perform abortions.

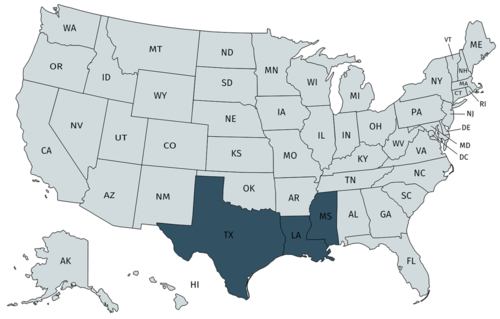

In the case, Louisiana tried to distinguish the effect of the Louisiana law from the effect of the Texas law which was ruled invalid. The state lost in the district court (the trial court) but managed to convince the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals that the Louisiana law would not place an undue burden on a woman’s right to an abortion like the Texas law did. The abortion providers appealed the Fifth Circuit ruling to the Supreme Court, claiming that the Fifth Circuit wrongly reversed the judgement of the trial court.

“Clearly erroneous” standard of review

In the Supreme Court, the abortion providers argued that the appeals court failed to follow the appropriate standard for overturning a trial court decision. According to standard of review principles, an appeals court may only overturn a trial court’s factual analyses if they are clearly erroneous. In other words, an appeals court is not to second-guess a trial court’s interpretations of facts unless they are clearly wrong.

In this case, when the trial court considered the effect of the Louisiana law, it determined the law would provide a great burden on women’s access to abortion and would not provide a real medical benefit to the state of Louisiana. With this factual analysis, the trial court followed the ruling in Whole Women’s Health, which had a nearly identical law and produced a very similar effect, to invalidate the Louisiana law.

Supreme Court ruling

Justice Breyer wrote the opinion of the Supreme Court, joined by Justices Ginsburg, Sotomayor and Kagan, ruling that the Louisiana law is unconstitutional. Chief Justice Roberts concurred that the law is unconstitutional, but he wrote a separate opinion.

The plurality opinion determined that the trial court’s conclusions based on the evidence before it were not “clearly erroneous.” Thus the Fifth Circuit should not have overturned the trial court’s conclusion that the Louisiana law is unconstitutional.

Regarding the effect of the law on women’s access to abortions, Breyer’s opinion for the Court pointed out that the trial court had considered the landscape of abortion access once the law went into effect. In evaluating the evidence, the trial court concluded that access to abortions would be limited to one clinic in New Orleans that would not be able to consume all of the state’s demand for abortions. Even for the women who were able to get appointments, the trial court determined, they would face significant burdens (like excessive driving times, crowding and long wait times). In recounting the evidence considered by the trial court, the Supreme Court determined that the trial court’s conclusion that the law would provide a substantial obstacle on women seeking abortions was not clearly erroneous.

Then the Court evaluated the trial court’s determination of the value, or medical benefit, that the Louisiana law would actually provide. The trial court found that law wouldn’t provide any real benefit, not in terms of the safety of medical procedures nor to women’s health. Again, the Supreme Court ruled the trial court had not made a “clearly erroneous” conclusion based on the evidence before it.

Finding the trial court had ample evidence before it to make its conclusions, the Supreme Court supported the trial court’s decision that the Louisiana law is unconstitutional. The Fifth Circuit should not have overturned it.

Concurrence: Chief Justice Roberts

Chief Justice Roberts joined in the ruling of the Court but wrote separately to state his rationale. Roberts clarified that his conclusion to invalidate the Louisiana law is based purely on stare decisis, the doctrine that courts must follow existing precedent. He noted that the Louisiana law at issue in this case is identical to the one from Texas that the Court invalided in 2016. Regardless of whether Whole Woman’s Health was right, he said, it is the law, and the Court must treat like cases alike. Roberts said the district court had ample evidence to follow the ruling in Whole Women’s Health.

Roberts also made the point that he believes the precedents, Casey and Whole Woman’s Health, do not conduct a balancing analysis. They do not weigh the burden on abortion against the benefit of the law. They simply ask whether the law’s burden on abortion is “undue” (i.e. if it places a substantial obstacle on a woman’s right to an abortion). If so, the law cannot stand. Roberts would reject the balancing analysis that the lower courts made and that the plurality opinion supported.

Dissent: Justice Alito

Justice Alito wrote the lengthiest dissenting opinion in the case. He was joined in whole by Justice Gorsuch and in parts by Justices Thomas and Kavanaugh. Sounding throughout the opinion is distrust of the doctors who pursued the challenge to the Louisiana law on behalf of abortion patients.

First, the opinion clarifies that the standard applicable to the case is the “substantial obstacle” test provided in the 1972 case, Casey. Then, Alito says the plurality and the Chief Justice got it wrong when they determined the Louisiana law provides no benefit by requiring abortion providers to have hospital privileges. Hospitals vet doctors much more stringently than clinics do, he said, and the additional requirements provide a benefit to women seeking abortions.

Regarding the plurality and Chief Justice’s conclusions on following Whole Woman’s Health, Alito says the cases are very different and Whole Woman’s Health is not controlling. Whole Woman’s Health involved a challenge to a law that already had taken effect, so the evidence brought to the trial court was not hypothetical. In this case, however, the Louisiana law had not gone into effect. Thus, the evidence produced was theoretical. No only does that mean Whole Woman’s Health is not controlling, but it also casts doubt on how the trial court evaluated the evidence.

Alito said, the trial court made incorrect presumptions about how the law would affect access to abortions in Louisiana. According to the opinion, the trial court should not have trusted that the doctors who brought the case to bring good evidence about their own attempts to gain the hospital privileges necessary under the Louisiana law. You can’t trust the doctors, he said, because of course doctors prefer less regulations and may not act in good faith when they are attempting to avoid a regulation. Alito argued the trial court’s trust of the doctors in providing evidence led it to make invalid conclusions about post-regulation abortion access.

Alito next argued that a challenge to an abortion regulation must include as plaintiff a woman who is seeking an abortion. In other words, it’s not the doctors who should be able to bring the case. In his view, there is a conflict of interest between abortion providers (who seek less regulation) and women seeking abortions (who seek safe access to abortions). The doctors cannot challenge the law on the women’s behalf; the women must assert their liberty interests themselves.

Other dissents

Justice Thomas dissented on his own to argue, first, that the doctors do not have standing to bring the case, and next, that the right to an abortion is not a constitutional right anyway. He would overrule Roe v. Wade: “the putative right to abortion is a creation that should be undone.”

Justice Gorsuch wrote separately to point out the conflict of interest between abortion providers and women seeking abortions. He also argued there are major factual differences between this case and the circumstances of Whole Women’s Health.

Justice Kavanaugh wrote separately to say additional fact-finding is necessary and that he would remand the case for the district court to evaluate it under the proper standard and also to address the standing argument.