The case that solidified the role of the judiciary

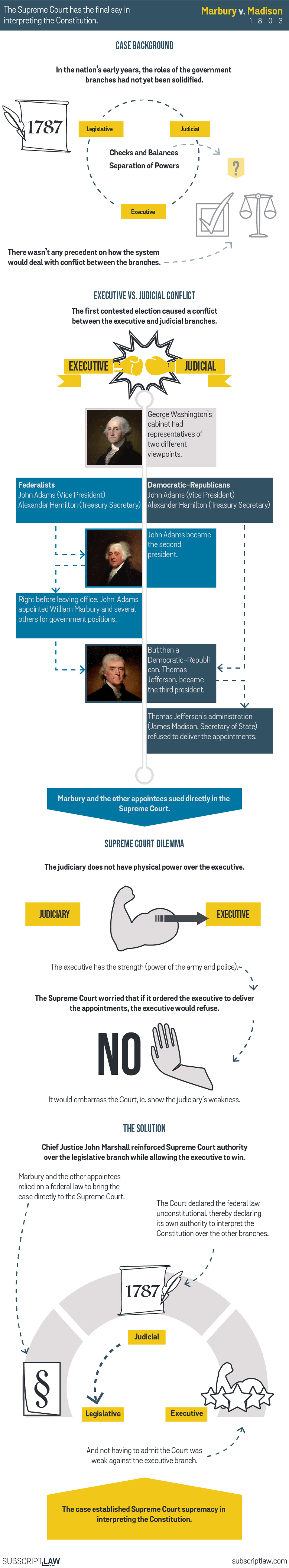

Marbury v. Madison is one of the most important cases in Supreme Court history — perhaps the most important. The Constitution was signed in 1787 with some very important principles that we take for granted today, like separation of powers and checks and balances. But there hadn’t been enough time for the principles to be put into action.

Marbury v. Madison brought the first major checks and balances issue to the Supreme Court. The case solidified the Supreme Court’s power to interpret the Constitution, and it also highlighted something else: the Court is not immune from politics. Here’s what happened.

When elections got hot

George Washington was not a fan of political parties. He thought partisanship would burden the potential to rule. However, the first political separation emerged within his cabinet. Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State, began voicing strong opinions about how the government should function, particularly in economic policies, foreign relations and relations with the states. Thomas Jefferson came to lead the Democratic-Republicans, while Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s Treasury Secretary, held strong for the opposing views of the Federalists. See more history and the main political differences here.

The first contested election came when George Washington refused a third term. John Adams, Washington’s Vice President and a Federalist, took the win. But after a 4-year term, the Democratic-Republicans grabbed the reins.

This case arose during the turnover between Adams and Jefferson.

The Adams appointments

Right before Adams was to leave office, he appointed several people into government positions. William Marbury was one of them. The appointments were not formally delivered before the Presidential turnover, so it would be Jefferson with the responsibility. Given the political differences, Jefferson refused.

The case

Marbury and the others who were refused their appointments sued directly in the Supreme Court. They asked the Court to issue a “writ of mandate” – a demand – for the new Secretary of State, James Madison, to get it done.

What, in theory, is a “demand”? A demand is a request with a degree of authority. But the authority of the Supreme Court is based on the threat of executive power. Marbury was asking the Court to issue a command against the highest executive authorities – the same authorities responsible for enforcing court orders in the first place.

Judiciary, the apolitical branch

The Court was created to be the apolitical branch. Intentionally so, the judges don’t have to worry about re-appointment or re-elections; their salaries cannot be diminished. These features are meant to keep courts away from political influence.

However, this case highlighted a significant dependence of the judiciary. It was a weakness that allowed politics to creep into the Court’s decision.

John Marshall, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, recognized this issue of enforcement. He did not want the Supreme Court to look weak. Remember, in the early days of the nation, the power of the three branches had no precedent. The system of checks and balances hadn’t even been proven effective. Marshall could not let the judiciary fall.

Rock, paper, scissors

Rock can’t beat paper, but it can crush scissors.

Knowing the judiciary could not win against the executive, Marshall (writing for the Supreme Court) decided to declare Court authority over the legislative branch. Never before had the Supreme Court used the Constitution to overrule Congress, but this day it did. Here’s how.

Marbury’s argument depended on an act of Congress (aka a federal law). The provision Marbury & Co. cited was one giving the Supreme Court authority to issue the “writ of mandate.” That provision would become the sacrificial lamb.

Writing for the Court, the Chief Justice declared the provision unconstitutional. The Chief Justice said the federal law giving the Supreme Court authority to deliver “writs of mandate” by direct Supreme Court appeal was unconstitutional. In the Constitution, the Supreme Court’s “original jurisdiction” was limited to “Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party.” Anything else (writs of mandate) would have to start in the lower courts.

With that ruling, the Court declared itself powerless in ordering the appointments yet eternally powerful over acts of Congress. In other words, the Court didn’t have to make an order against the executive that it feared wouldn’t be respected. But it still credited itself with the most important judicial power that we recognize today: the power of Congressional review.

Judicial review over the executive and states

In Marbury v. Madison, the Court declared the judiciary able to overrule acts of Congress because it has the final say on interpreting the Constitution. The Constitution also takes precedence over executive actions and state governments when the executive and state authorities come into conflict with the Constitution.

Thus, with the Marbury v. Madison ruling, the Court was poised to overrule any government action if the Court determined the action violated the Constitution. We take that for granted today, and we can visit some of the most controversial rulings in American history as evidence of its power.

Authority over states

The Supreme Court has exercised its authority controversially in overruling states on civil rights issues. In the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, for example, the Supreme Court ruled to desegregate all public schools (state institutions) because it determined state laws allowing segregation on the basis of color were unconstitutional.

In following years, the Supreme Court made a number of other rulings determining that states were violating individuals’ liberty rights as guaranteed by the Constitution. These “substantive due process” rights include the right to marry someone of a different race (Loving v. Virginia); the right to an abortion before the point of viability (Roe v. Wade); the right to privacy in sex practices (Lawrence v. Texas); and the right to marry someone of the same sex (Obergefell v. Hodges).

Authority over the executive

Thanks to Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court can check executive power too. When someone believes an executive agency or even the President has overstepped constitutional boundaries, the judiciary can help.

In 1973 lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force brought suit against the U.S. Defense Department Secretary asking the courts for constitutional help. Sharron Frontiero alleged a military policy to give spousal benefits only to wives of military members violated the Constitution. She won, with the Supreme Court ruling the executive agency had violated the Constitution’s Equal Protection clause by discriminating the basis of sex in its military benefit policy (Frontiero v. Richardson).

The “Travel Ban” case is a more recent example of a request for executive review that went the other way. Muslim individuals, states and civil rights groups alleged the President and Department of Homeland Security had restricted the immigration of individuals from Muslim countries in violation of the Constitution’s First Amendment. The Court ended up ruling for the government, saying the Constitution gives the President broad authority in the realm of immigration.

For more information on the legacy of Marbury v. Madison, see this lesson plan overview from USCourts.gov.