Laws Relating to Government Electronic Surveillance

Constitution • Congress • Executive • Federal Courts • State Governments

Introduction

The Fourth Amendment protects us against unreasonable search and seizure, but its meaning has changed over time. When the Fourth Amendment was written, the Founders weren’t thinking about phones and email; they were thinking about homes and coats. The Fourth Amendment’s protections against “unreasonable search and seizure” have evolved since then. By the end of the 1960s, the Supreme Court had clarified that the Fourth Amendment applies to people, not places. If you’re in a phone booth, you may still have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” even though the property isn’t yours (Katz v. U.S (1967)).

A next major step for the Fourth Amendment was thinking in terms of third parties, or companies that have access to our personal records. When you give your information to banks and telephone companies, the Supreme Court ruled, you actually don’t have a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” That’s because you choose to give the information. It’s a voluntary transfer of personal information. However, a Supreme Court case from the 2018 indicates the “voluntary” theory may be changing (Carpenter v. U.S.). See our Cybersecurity and Law Enforcement report for more information.

Congress has stepped in with a number of federal laws to fill in gaps in Fourth Amendment protection and to clarify the rules. Whether under the Fourth Amendment or another federal law, the government usually must have a good reason to access individuals’ personal information.

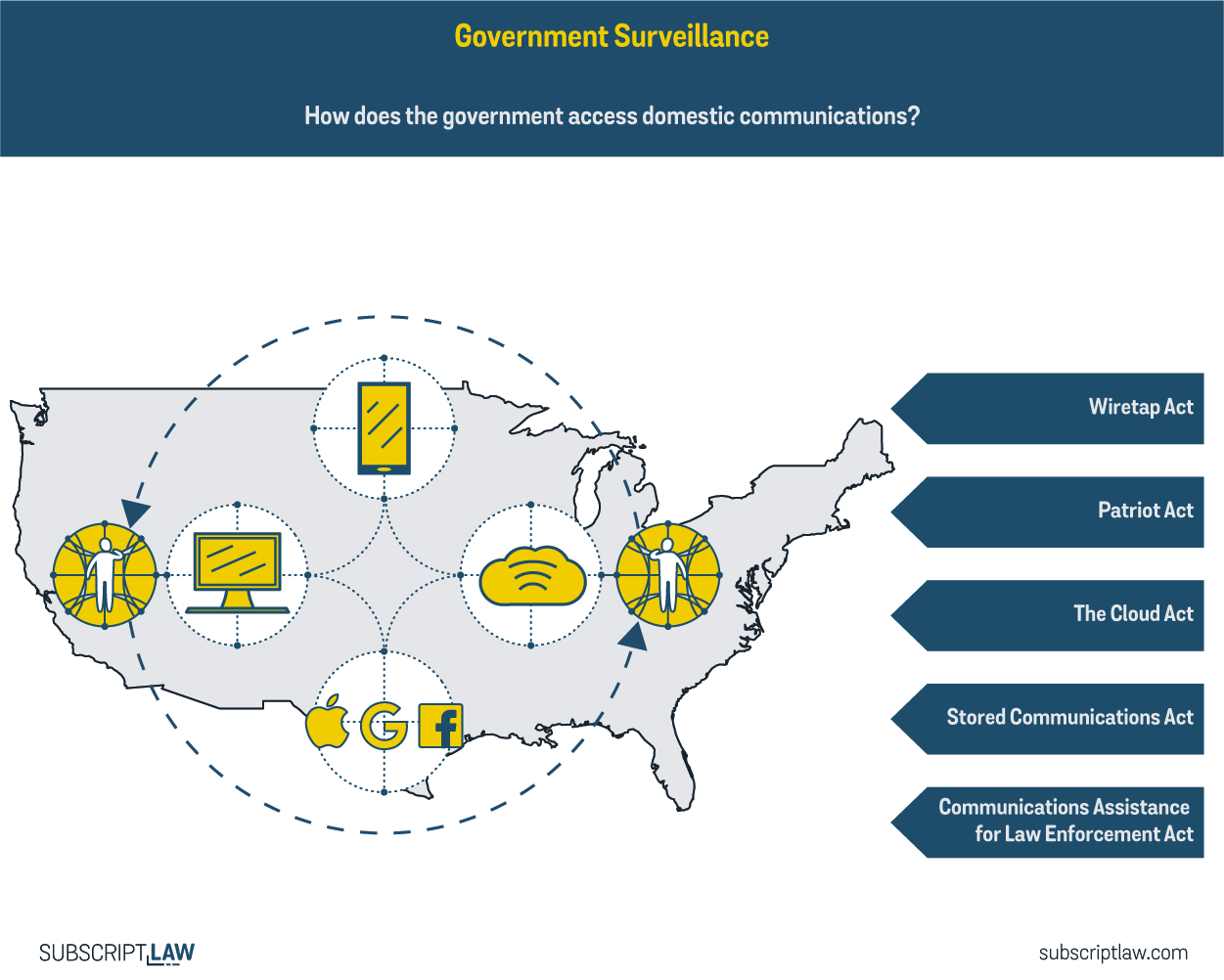

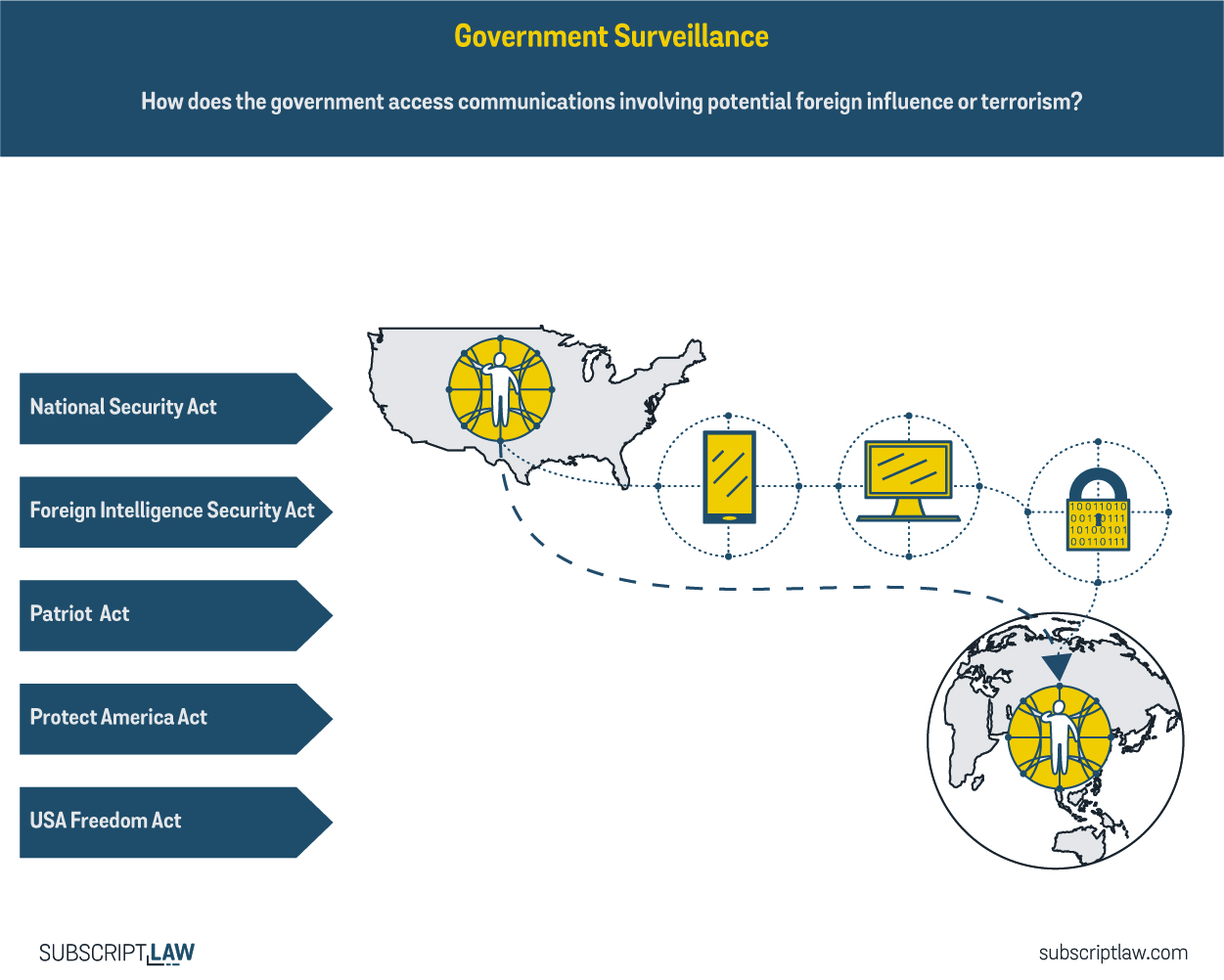

This report outlines the laws relating to government surveillance. The infographics list the major laws in two different categories because the laws differ depending on the government’s reasons for seeking the information. One set of laws apply when the government is investigating crimes of a domestic nature and another set apply when the government is investigating crimes involving foreign influence or terrorism.

Domestic Communications, Domestic Crimes

Communications with Foreign Influence or National Security Ties

Legal Landscape: Government Electronic Surveillance

Summaries of laws relating to government surveillance

The Constitution

The Fourth Amendment protects individuals against unreasonable search and seizure by the government. For a search to be reasonable, the government generally must have “probable cause” that a crime has been or is being committed, and the government must first get a search warrant (although there are many exceptions to the search warrant part). The 4th Amendment can apply to computerized data. However, because it was conceptualized in terms of physical searches (versus electronic), its application to electronic data has been strained. See the Judicial section for a discussion of how the 4th Amendment has been applied to electronic data.

The First Amendment, which protects our rights to free speech, to peacefully assemble and to petition our government for redress, is potentially implicated in situations of electronic surveillance. If the government is stalking us, we are less likely to feel comfortable to speak out on controversial issues, especially those critical of the government. See, for example, this article on excessive wiretapping of Dr. Martin Luther King by the FBI during the civil rights movement. Also check out this article noting the counterplay between the 1st and the 4th Amendments and highlighting the relationship of electronic communications to political movements of today.

See the Legislative section for laws that address more specifically the limits of government power. Note the difference between laws governing surveillance of Americans on domestic issues versus the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which gives the government more freedom to listen in on people if they are suspected to be connected to a foreign power.

Congress

The National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It was the major restructuring of the U.S. government after World War II. The CIA was the U.S.’s first peacetime intelligence agency. This Legislative section would normally include the statutes creating the other two agencies greatly involved in electronic surveillance, but the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the National Security Agency were not created by statute. Rather, they were created by executive action. See Executive section.

The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (aka the “Wiretap Act”). Title III of the Act controls the interception of wire and oral communications by both the government and by private parties. The act sets out detailed procedures that the federal government must follow before surveilling people, including submitting a sworn application to a federal judge with the details of the communications to be intercepted (location, reasons, duration, identities of persons to be surveilled, accounting of other less-intrusive techniques that have been tried). A warrant granted under the Act must be executed as soon as possible, does not extend past 30 days, and it terminates as soon as the objective is completed. If the government gathers evidence without a warrant, the evidence is not admissible in court.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) of 1978 controls how the government can use physical or electronic surveillance to collect intelligence between foreign powers and agents of foreign powers suspected of espionage or terrorism. The government can use electronic surveillance on property owned exclusively by foreign powers for the purpose of gathering information potentially needed to protect the United States from attack. The government can do this for one year without a warrant, as long as the surveillance is not likely to gather communications of which a United States citizen is a party. The Act created a special federal court for the purpose of overseeing requests by government agencies for foreign intelligence surveillance warrants. See United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISA Court) in the Judicial section.

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 extended 4th Amendment protections to electronic communications. Title II is called the Stored Communications Act, which requires a warrant or consent before surveillance is conducted, and it establishes procedures that the government must follow in ordering telecommunications providers to turn over electronic communications information. The act also establishes standards for what constitutes “reasonable grounds” for a court to issue a warrant or a subpoena of information. The Act addressed a gap in 4th Amendment protection created by the Supreme Court’s “third party doctrine.” See the Judicial section for a discussion of this doctrine.

The Patriot Act of 2001 permitted the federal government to take enhanced surveillance procedures of suspected terrorists (both American and foreign), broadened wiretapping powers, extended the government’s power to demand electronic communications, and loosened federal government search warrant requirements in cases of suspected terrorism.

The Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act of 2006 required that telecommunications companies cooperate with government requests for electronic information.

The Patriot Sunsets Extension Act of 2011 extended several major provisions of the Patriot Act when the Patriot Act was set to expire, including the right to wiretap an individual (rather than a device, aka “roving wiretap”), the right to demand companies to turn over business records, and the right to conduct surveillance of individuals suspected of terrorism (aka the “lone ranger”).

The Protect America Act of 2007 altered the definition of “electronic surveillance” under FISA so that the government could, without warrant, survey even Americans’ communications if the person to be surveilled is outside the United States. The Act also said that if the government provides certain certifications on the type of information they are seeking, then telecommunications companies must comply with government requests. The government must certify, for example, that “a significant purpose” of the collection is to obtain foreign intelligence information; and that the government is making efforts to minimize the data it collects on Americans. Telecommunications companies are immunized from suit for actions they take to comply with FISA orders.

The USA Freedom Act of 2015 extended many provisions of the Patriot Act (upon the Patriot Act’s expiration), but it ended the National Security Agency’s mass telephone data collection program. This part of the Patriot Act that was not extended prevents the NSA from automatically collecting masses of telephone data on Americans and instead limits the NSA to seek information only on specific people by getting a federal court order.

The President and Executive Agencies

Domestic Investigations:

The Department of Justice (DOJ) is responsible for federal law enforcement. It conducts investigations on U.S. citizens regarding potential federal crimes. DOJ sub-agencies apply to federal court to get search warrants to intercept electronic communications of Americans. In most cases, the agencies must follow the warrant or consent requirements of the 4th Amendment as well as the requirements of other relevant federal laws (see the Legislative section for some of these laws).

The DOJ investigative agencies include, for example:

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

- Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF)

- United States Secret Service (USSS)

- Homeland Security Investigation (DHS/HSI).

The investigative agencies work with the Office of the United States Attorneys, also within DOJ. The Office of the United States Attorneys represents the government in court. This includes:

- Prosecutors in federal criminal cases (United States vs. Suspect-Defendant)

- Attorneys defending the government in civil lawsuits (e.g. Citizen/Company vs. United States Agent/Agency)

Foreign Intelligence

In addition to investigating domestic crimes, the federal government also gathers foreign intelligence for the interests of national security. In cases of foreign intelligence gathering, the 4th Amendment requirements may be relaxed. For example, the law governing surveillance of potential foreign spies includes procedures that allow surveillance without a warrant (see Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in the Legislative section).

Sixteen federal agencies make up the U.S. Intelligence Community, led by the Director of National Intelligence. The agencies cited most commonly in relation to surveillance and use of data are the National Security Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Central Intelligence Agency.

National Security Agency (NSA) operates under the Department of Defense. It is primarily responsible for investigating cryptic communications relating to United States national security. It tunes in to communications sent through spy satellites, faxes, phones and computers, and decrypts them for our national security interests. Though the agency operates generally for foreign intelligence, the NSA also targets communications of American citizens.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) operates under the U.S. Department of Justice and is not connected to the Department of Defense. The FBI primarily is responsible for surveillance relating to domestic issues, but it crosses the line into foreign intelligence gathering. The agency has jurisdiction to investigate all federal crimes, from government fraud and organized crime to domestic terrorism.

The NSA and the FBI are the two federal agencies that were created by executive acts, rather than by an act of Congress. Because they were not created by Congressional acts, they are arguably not as strictly bound as agencies that have explicit limits set out in legislation. The NSA and the FBI are the two agencies most often requesting warrants under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). To obtain a FISA warrant, the federal agency must show the court that the target is a “foreign power” or an “agent of a foreign power.” The FISA warrant process is controversial, as discussed in the Judicial section on the FISA Court.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is another federal agency that collects electronic information for the government. The CIA is meant to conduct foreign intelligence missions, as opposed to domestic information-gathering. But it has engaged in spying on Americans, starting with “Operation Chaos,” a domestic spying mission created under President Johnson for the purpose of gathering information on anti-war (anti-government) activities. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, legislation eased information-sharing across federal agencies, and the CIA became a participant in domestic surveillance missions of the FBI.

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan signed Executive Order 12333 which expanded U.S. intelligence agencies’ power to collect data. Read how it impacts policy in this article referencing how the NSA might use it.

Federal Courts

The 4th Amendment was written to apply to physical searches, not to electronic searches. As new technologies emerged, courts have tried to apply the 4th Amendment to electronic data, but as a result, the Amendment’s effect has been watered down. Here are some relevant rulings that apply to government interception of communications that are not foreign intelligence-related.

Olmstead v. United States (1928) was an early ruling in which the Supreme Court did not recognize government wiretapping as a “search” or a “seizure” because the wire was tapped outside the suspect’s home and there was not a physical breach into a place. Thus the Court said the 4th Amendment did not apply and the federal agents did not need to get a warrant or consent to wiretap the lines outside of the suspect’s home. The ruling has since been overruled in the next case:

In Katz v. United States (1967), the Supreme Court overruled Olmstead, deciding that the 4th Amendment protects a person, not a place. That meant that it could apply to any intrusion where a person had a reasonable expectation of privacy. In this case, the government had placed a listening device outside of a public phone booth where the suspect was taking calls. The Court ruled the 4th Amendment applied and thus the government would have needed to get a warrant.

Other rulings on the 4th Amendment:

The 4th Amendment does not apply to information voluntarily handed over to a third party (the “third party doctrine”).

In U.S. v. Miller (1976), the Supreme Court said that the government could get access to bank records if the information was voluntarily given to the bank. The Court basically said you can’t expect 4th Amendment privacy if you are offering the information over voluntarily. Under the same theory, the government can get access to telephone numbers you dial because you are voluntarily giving those numbers to the telephone company. See Smith v. Maryland (Supreme Court 1979). The legislature passed the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (see Legislative section) to fill in the gaps to citizen privacy protection that were left by the third party doctrine.

The 4th Amendment does not cover private searches.

The federal appeals courts (Circuit Courts of Appeals) have made numerous rulings to determine whether the government is involved in a search. For example, in United States v. Smith, a 2004 appeals case (8th Circuit), police detectives subtly suggested that a FedEx employee could open a package suspected to have drugs. The court held that then the government was not controlling the search so it did not need to get a warrant. On the other hand, in United States v. Souza, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals (2000) said the government was too pushy in encouraging a UPS employee to open the box, so the failure to obtain a search warrant invalidated the evidentiary content. Similar rules would apply to government pressure of private parties to search electronic content.

The 4th Amendment applies to monitoring for national security interests conducted by the President.

In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. United States District Court for Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division that even the president must get a warrant before conducting surveillance of U.S. citizens, and the exception for national security reasons is not easy to get. Nixon had been listening in on leaders of the far-left White Panther Party without a warrant and supported the action based on domestic security threats. The Supreme Court said the government must get a warrant before conducting surveillance even in cases of domestic security threats.

See this article in the Harvard Law Review for a detailed case study of the 4th Amendment as applied to electronic searches. And for even more cases on the 4th Amendment and electronic surveillance, see here.

A Unique Federal Court:

When it comes to national security and investigation of foreign spies, the government can watch people without the protections promised by the 4th Amendment. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (see Legislative section) defined the rules in this area and created a unique federal court to handle such warrant requests. In theory, the government is supposed to minimize the communications it intercepts of which an American citizen is a party, but in practice that is not clear.

The United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (“FISA Court”) is a unique federal court created by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. This court oversees requests for warrants on foreign spies. The requests are made mostly by the National Security Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Court proceedings and orders are kept secret because of the sensitive nature of information presented. The court’s operations are controversial because the court’s actions are not transparent, and the court hears only one side of the case: the government’s. It is extremely rare that this court denies a warrant. In fact, between the years since its start in 1979 and 2016, out of the 39,654 applications for surveillance orders, the FISA court denied only 51 (as reported by Electronic Privacy Information Center). Further, appeals are very rare. For more information on the FISA Court including some opinions and orders, see here.

Recently, the FISA Court has been in the news for granting a warrant to target communications of a Trump campaign adviser, Carter Page, based on Page’s ties to Russia. The FISA Court also came into the spotlight when Edward Snowden leaked information about NSA surveillance of Americans through a FISA order.

State Governments

States are bound by the 4th Amendment and Supreme Court interpretations of it (see the Judicial section). For example, states cannot, without a warrant, intercept communications where a person has a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” State enforcement authorities have their own policies on how they conduct searches, but they all must be Constitutionally-compliant (not violate the 4th Amendment). See, for example, a New Jersey law enforcement policy on searches.

In addition, many states have created legislation stronger than the 4th Amendment to protect their citizens from unreasonable search by the state government, just as federal legislation limits the federal government. For example, many states have enacted a state version of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act (the federal version, you can find in the Legislation section above).